Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a condition that describes the nausea, vomiting, and/or retching that occurs in the immediate 24 hours following a surgical procedure [1]. 10 to 30% of all surgical patients experience PONV, but this rate can reach as much as 80% among patients undergoing high-risk procedures [1]. In past surveys, the majority of patients have claimed that PONV is the most disagreeable of all post-anesthesia outcomes, including pain [2]. Not only is the condition undesirable, but it can also lead to patients staying longer in the post-anesthesia care unit, thereby augmenting healthcare costs and reducing patient satisfaction [1]. Consequently, clinicians should consider helping patients avoid this condition by administering appropriate prophylactic treatments. One such preventative treatment for nausea and vomiting is olanzapine.

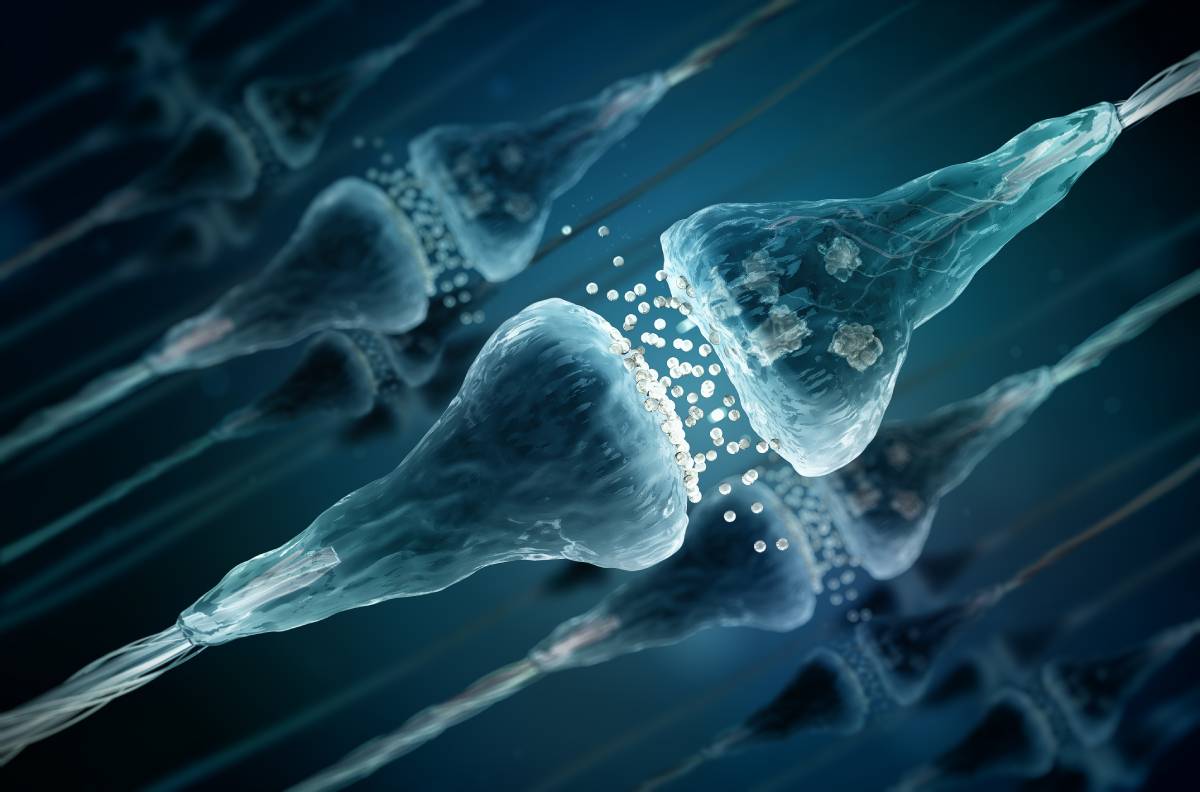

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic agent (AAPs) [1]. AAPs are notable for having an atypical binding profile to several central nervous system receptors [3]. Olanzapine’s anti-emetic properties stem from its specific binding profile [4]. Because it binds to serotonin receptors 5HT2 and 5HT3, as well as dopamine receptor D2, olanzapine can successfully suppress nausea and vomiting [3]. Researchers first studied these qualities in the context of post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting. Upon taking olanzapine, chemotherapy patients reported significant reductions in nausea and vomiting, compared to those who were not given olanzapine [5]. Olanzapine has also been studied in the context of palliative care where, again, data demonstrated its effectiveness as an anti-emetic [3].

In 2013, Ibrahim et al. conducted the first investigation of olanzapine’s effects on PONV [4]. The researchers divided 82 breast surgery patients into four groups: a control group who received placebo, two groups who received either 5 mg or 10 mg of olanzapine preoperatively, and one group who received ondansetron, another anti-emetic [4]. They did not note a clinically significant difference between the groups in reported rates of PONV from 0 to 2 hours following surgery [4]. However, patients receiving olanzapine reported significant reductions in PONV compared to placebo for the rest of the 24 hours [4]. Fortunately, this regimen of olanzapine was not associated with induction of hyperglycemia, notable weight gain, or significant sedation, which are associated with other uses of the drug [4]. To address this short-term inefficacy, the researchers recommending pairing olanzapine with another antiemetic effective during the first two postoperative hours [1, 4]. Though these results are promising, olanzapine still needs to be tested in other surgical contexts to ensure reliability.

More recently, scientists have studied ambulatory surgery patients’ experiences with PONV after taking oral olanzapine or a placebo [2]. 35 million ambulatory surgeries occur in the United States every year, with 37% of ambulatory surgery patients reporting PONV [2]. To analyze the relationship between olanzapine and nausea and vomiting following ambulatory surgery, a 2020 study followed 140 adult female patients scheduled for plastic or gynecologic surgery with general anesthesia [2]. The researchers divided the patients into two groups, only one of which received oral olanzapine [2]. Clinicians gave both groups ondansetron and dexamethasone [2]. Compared to the control group, patients who received olanzapine were 60% less likely to experience PONV [2]. Nevertheless, several factors require further investigation, including how the anesthetic sevoflurane interacted with the olanzapine [2].

Unfortunately, studies of olanzapine in the postoperative context remain limited in number. Hopefully, research will continue to allow the emergence of a more definite picture concerning when and how oral olanzapine can prevent PONV.

References

[1] V. S. Tateosian, K. Champagne, and T. J. Gan, “What is new in the battle against postoperative nausea and vomiting?,” Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology, vol. 32, no. 2, p. 137-148, June 2018. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2018.06.005.

[2] J. B. Hyman et al., “Olanzapine for the Prevention of Postdischarge Nausea and Vomiting after Ambulatory Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Anesthesiology, vol. 132, p. 1419-1428, June 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003286.

[3] G. Saudemont et al., “The use of olanzapine as an antiemetic in palliative medicine: a systematic review of the literature,” BMC Palliative Care, vol. 19, no. 56, p. 1-11, April 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.018.

[4] M. Ibrahim, H. I. Eldesuky, and T. H. Ibrahim, “Oral olanzapine versus oral ondansetron for prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting. A randomized, controlled study,” Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia, vol. 29, p. 89-95, January 2013. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egja.2013.01.002.

[5] C. M. Hocking and G. Kichenadasse, “Olanzapine for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review,” Supportive Care in Cancer, vol. 22, p. 1143-1151, February 2014. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2138-y.